The Polish Anti-tank Squadron in Oosterbeek

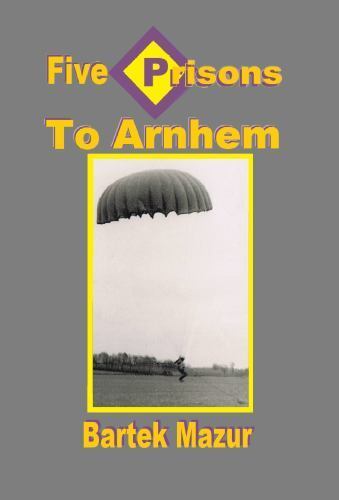

The book ‘Anti-tank Artillery Squadron in the Battle of Arnhem’ was published in 2022. A booklet full of facts and analysis on the deployment of the Polish anti-tank unit of the Parachute Brigade. Because of this focus, it also gives great insight into an often underexposed part of the battle on the north side of the Rhine.

The deployment of the 1st Polish Independent Parachute Brigade in Operation Market Garden

Without detailing the plans here, the plans at the start of the operation were to transfer the brigade from Britain to Arnhem in four stages. The bulk, the lightly armed paratroopers were to be dropped southeast of the Arnhem bridge near Elden on the third day (i.e. 19 September). For more details on the plans and the total Polish deployment, see our dossier Driel 44 (n Dutch).

The anti-tank artillery, and their jeeps with supplies would land via gliders on day two and three on the north side of the Rhine. The heavier equipment was en route by road via Belgium. Polish ambulances, for example, eventually arrived in Driel.

The photo below shows a 6-pdr gun being loaded into a glider. The second photo shows such a piece behind a jeep. These are British troops, by the way. Of the Polish pieces only one photo is known to us (see photo above this post).

Since the gun crew of the 6-pounder anti-tank guns consisted of more than the two men who could fly with the gliders, the rest would be dropped as paratroopers. Until the units were back together, the plan was that the glider pilots would rotate in as gun crews.

So much for the plans. Things ended up working out differently.

Day two: The first guns reach Oosterbeek

On the second day of the landings, 18 September, the gliders still fly and land fairly undisturbed on the planned landing zone ‘S’ (LZ-S) near Wolfheze. From there, they drive via Heelsum to Oosterbeek, where the pieces are brought into position close to the British headquarters at Hartenstein. They are positioned roughly around the junction Oranjeweg – Utrechtseweg and Sonnenberglaan.

This the book charts nicely based on the reports of Lieutenant Mleczko who traced the position of the guns on the map. As the book records, 18 Poles – supplemented by the glider pilots brought five guns into position.

Day three: big loss of material and men

On the 19th, the paratroopers’ flight is cancelled due to fog at the airfields. The second group of gliders with guns did leave and landed at LZ-L north of Oosterbeek around Johannahoeve in the late afternoon. At the time, there was heavy fighting around that area between the now advancing Germans and the British defending there. As a result, a lot of equipment was lost during the landing and, of the ten overflown guns, only two eventually left the landing area while one was immediately deployed on the edge.

Of the eight combinations of jeeps with trailers, only two leave the landing area. Apart from equipment, the Poles also lose men (read Edward Trochim’s story) as they are killed, wounded or captured right away.

When the rescued jeeps, guns and trailers reach the others in Oosterbeek via Wolfheze, 44 Poles with seven guns are available on the north side of the Rhine.

From Hartenstein to the southside of the perimeter

The book gives a detailed account of how the pieces support the battle on the north-west side of the Oosterbeek perimeter as the Germans advance there and try to take the area occupied by Allied troops.

A the end of Wednesday it becomes clear that the Polish anti-tank units are needed to help defend the south side of the perimeter where the Germans are trying from both the west and the east to cut off the British from the Rhine and thus from the XXX-Corps advancing from the south. During this transfer of pieces, the Poles are shelled and lose several more men.

On the southern side of the perimeter, they then take position near the Old Church and at the T-junction Kneppelhoutweg, Benedendorpsweg. The photo below is an iconic photo from the battle near Oosterbeek and shows a 6-pound gun manned by men from No. 26 Anti-Tank Platoon, 1st Border Regiment. The deployment of the Polish pieces will have looked similar.

The unit’s ‘infantrymen’

While part of the anti-tank unit fiercely battles in Oosterbeek, the other part waits for their flight to the battlefield. This finally happens on the afternoon of 21 September. The drop zone has then moved from the Elden area to Driel. The men of the anti-tank unit who then land in Driel, in the absence of their anti-tank guns assignment, are deployed as regular infantry in the defence of Driel against German attacks.

Attempting to cross the Rhine on the night of 22-23 September, just over 50 men of the 3rd Battalion, 8th Company reach the north bank. They take up positions on the south-west side of the perimeter around the Kneppelhout road already mentioned.

On the second attempt, on the night of 23-24 September, over 150 men reached the north bank from Driel. These included the ‘infantrymen’ of the anti-tank unit. Because by then a large part of the guns had been knocked out, they were deployed at van Lennepweg to help defend the perimeter there while other troops supported the British at Stationsweg in Oosterbeek.

In more detail

The book obviously covers the timelines, locations and, for many of the fallen, the circumstances of their deaths in much more detail.

Because of the details and the use of not always well-explained abbreviations, it is not a bookt that reads easily but the authors Nigel Simpson and Mateusz Mroz can be forgiven. The book is a must-have for anyone with an above-average interest in the Polish effort, especially as it highlights the often underexposed role of the Poles in Oosterbeek.

In the near future we will use this information to supplement Polish War Graves’ pages with this information, for example the two heroic actions of Karol Standarski, who paid for this with his life in Oosterbeek.

The booklet is available in the Netherlands from ‘de Vrienden van het Airborne Museum‘.