Every Polish liberator had his own story about the route that brought them to the Netherlands. In ‘Five Prisons to Arnhem’ we are introduced to the story of Bartek Mazur. The book was published in the US in 2022, but is now also available in the Netherlands through Polen in Beeld and the Driel Polen Foundation*.

Common routes

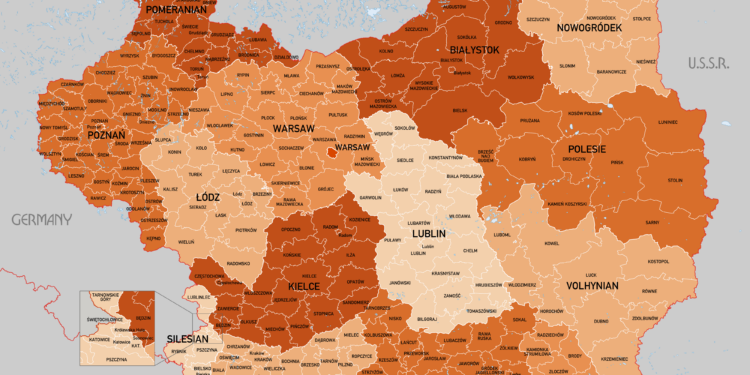

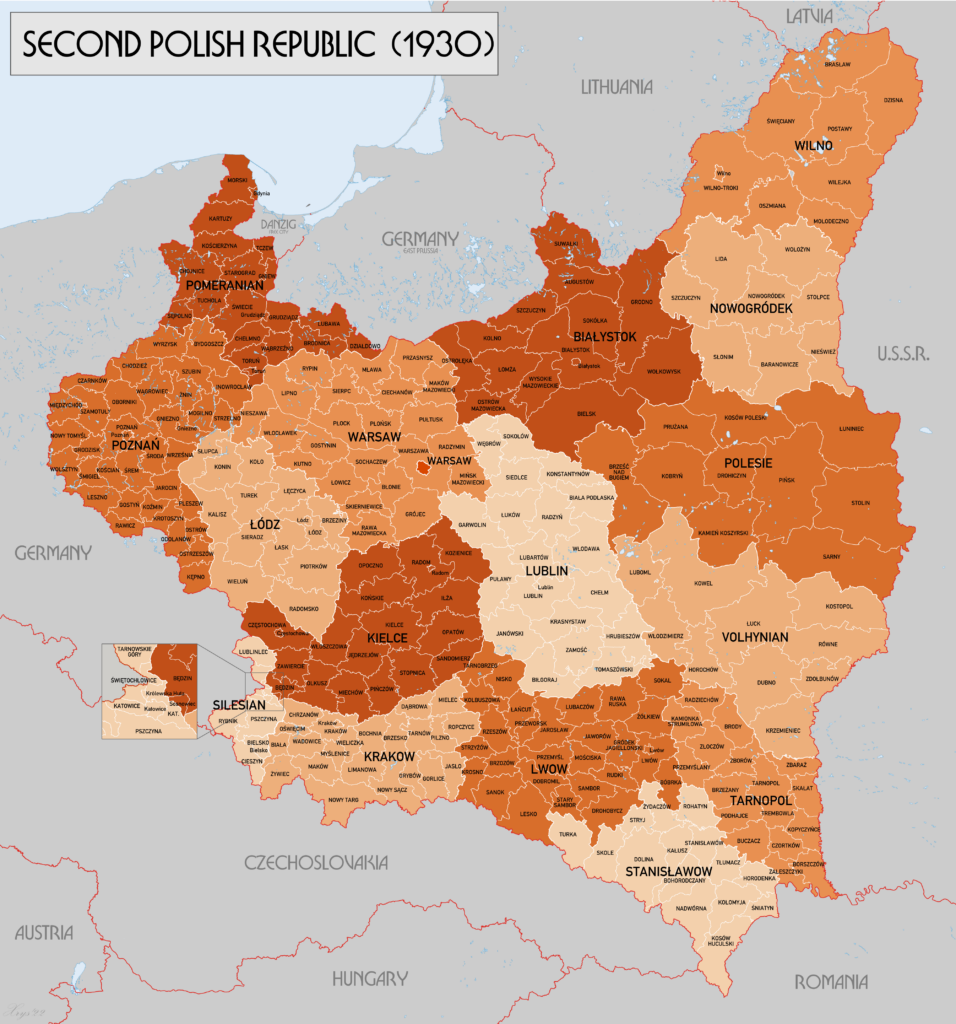

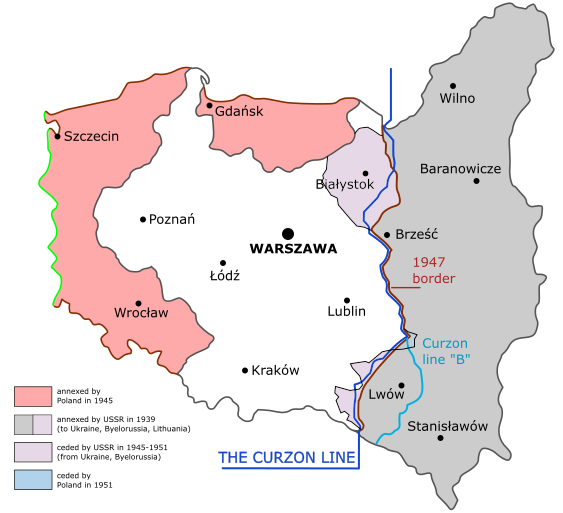

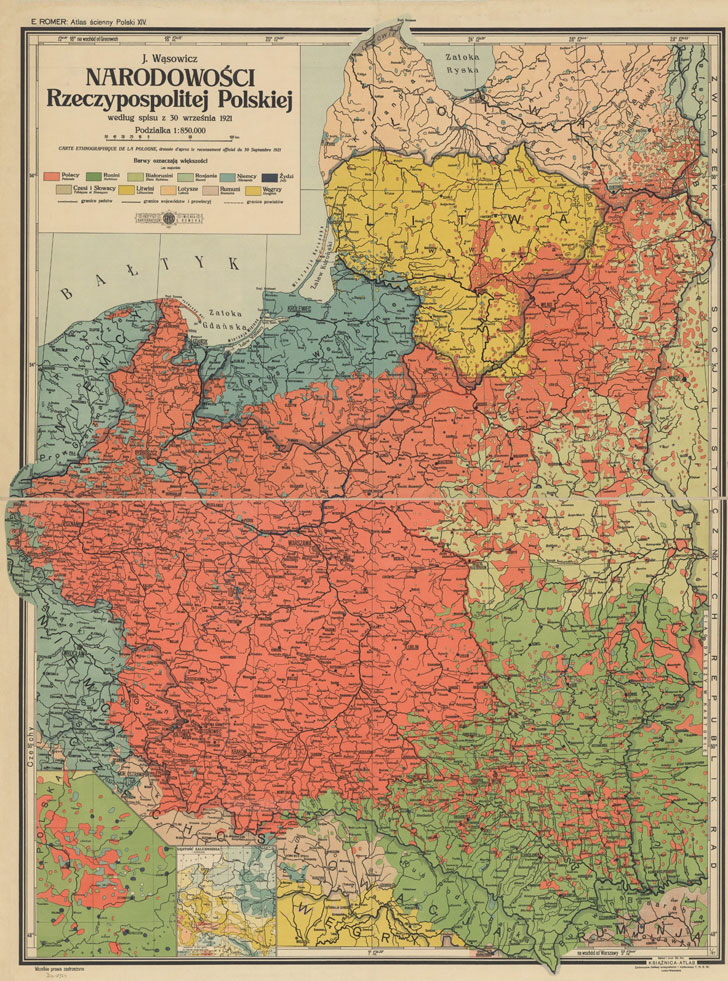

There are roughly three common routes how our Polish liberators came west to join the parachute brigade or the armored division. First, after the autumn campaign of 1939, many soldiers emigrated to Romania and Hungary to travel to France to join the Polish armed forces. A second route followed Poles who were deported by the Soviet to labor and punishment camps deep in the Soviet Union. They were released after the Soviets also entered the Allied camp and then traveled via the Caucasus, Persia and Africa to the UK. The third route were the Poles who were unlucky enough to come to the west via German conscription or forced labor. They defected to the Allies as soon as they had the chance.

This story by Bartek Mazur takes a different route.

Past five prisons

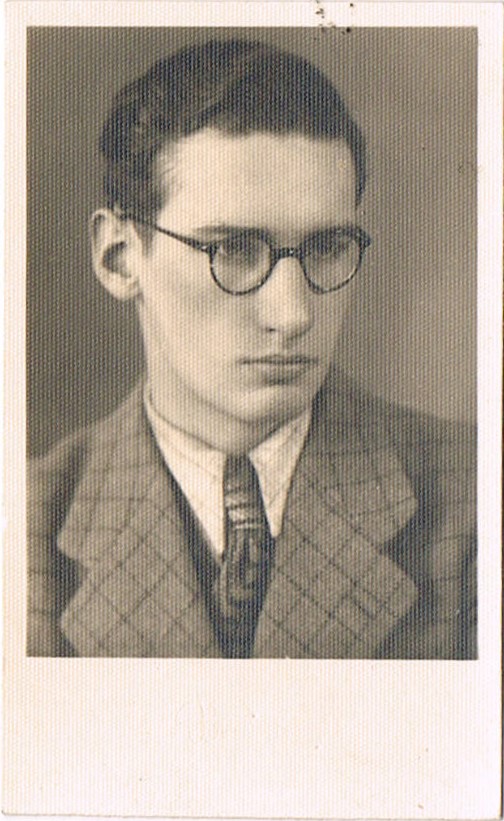

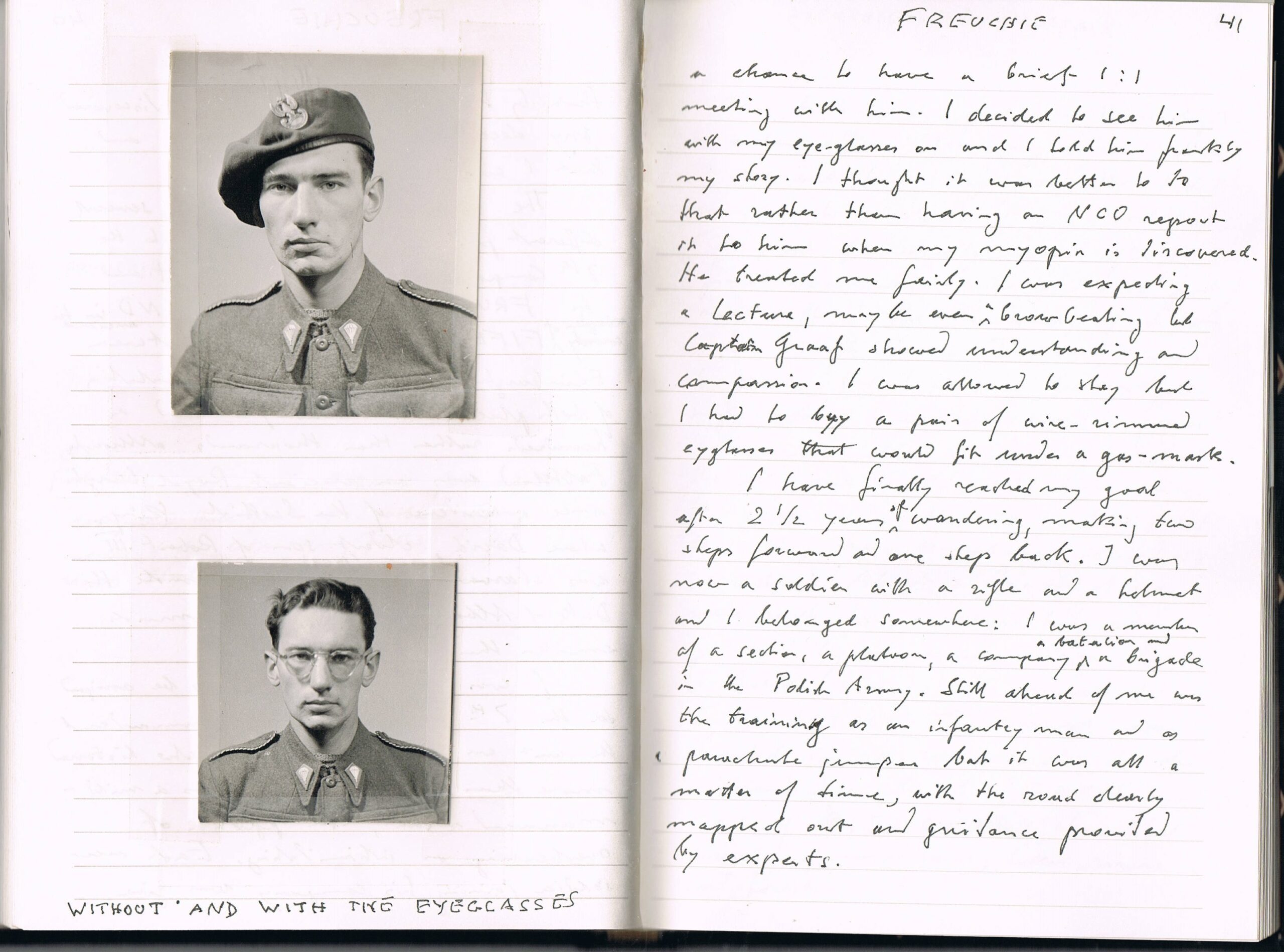

Bartek Mazur grew up with a talent for languages and the piano. His plans at the end of the lyceum were disrupted by the German invasion in 1939. In 1940 he heard that his father had been murdered as a political prisoner in Mauthausen. That makes him determined to get revenge. Together with two friends, he decides to travel through Germany to Switzerland to report to the Polish consulate there. Everything seems to be going well until they are arrested in Switzerland. Then his journey through the five prisons of the title begins. His journey takes him to France and Spain before the final confinement in the UK.

As can be deduced from the title, that is not the end point. He joins the paratroop brigade and is deployed to Driel as part of Operation Market Garden.

The writer and his book

The book was written by Bartek Mazur himself who wanted to record his memories for his children. His daughter Edina showed the texts to a publisher who said: “You have a book!”. As we understood from the daughter, it still required some effort to convert the handwritten memoirs into a publishable text supported with images, but then there was the book.

And that effort pays off. It is a book that is pleasant to read with an attractive style. The writer, who became a psychiatrist and visual artist after the war, and his daugther as editor, find a good mix of memories and reflections on his experiences.

The daughter’s foreword and afterword also strengthen the story with good additions. It is bizarre, as described in the foreword, that the Mazur family is sitting at the table when they think they hear their arrested father knocking on the door with his walking cane. Unfortunately he is not there and later this event turns out to correspond to the moment of death in Mauthausen.

Driel

Bartek and his best friend Sławek were part of the paratroopers who crossed the Rhine from Driel on the second attempt. When Bartek wanted to get in, the boat was full and his friend left for the fighting in Oosterbeek. Bartek stayed in Driel. When the battle in Oosterbeek was ended and troopswithdrew accros the Rhine, Sławek did not return from Oosterbeek. They only see each other again after the war.

Reflections

From the perspective of the writer himself, who as an aging man looks back on his young self, it could be called a ‘bildungsroman’ in literature, in addition to the ‘road trip’ that it also is. It is interesting to read how the psychiatrist analyzes an incident in Driel and how his feelings of revenge against the Germans developed.

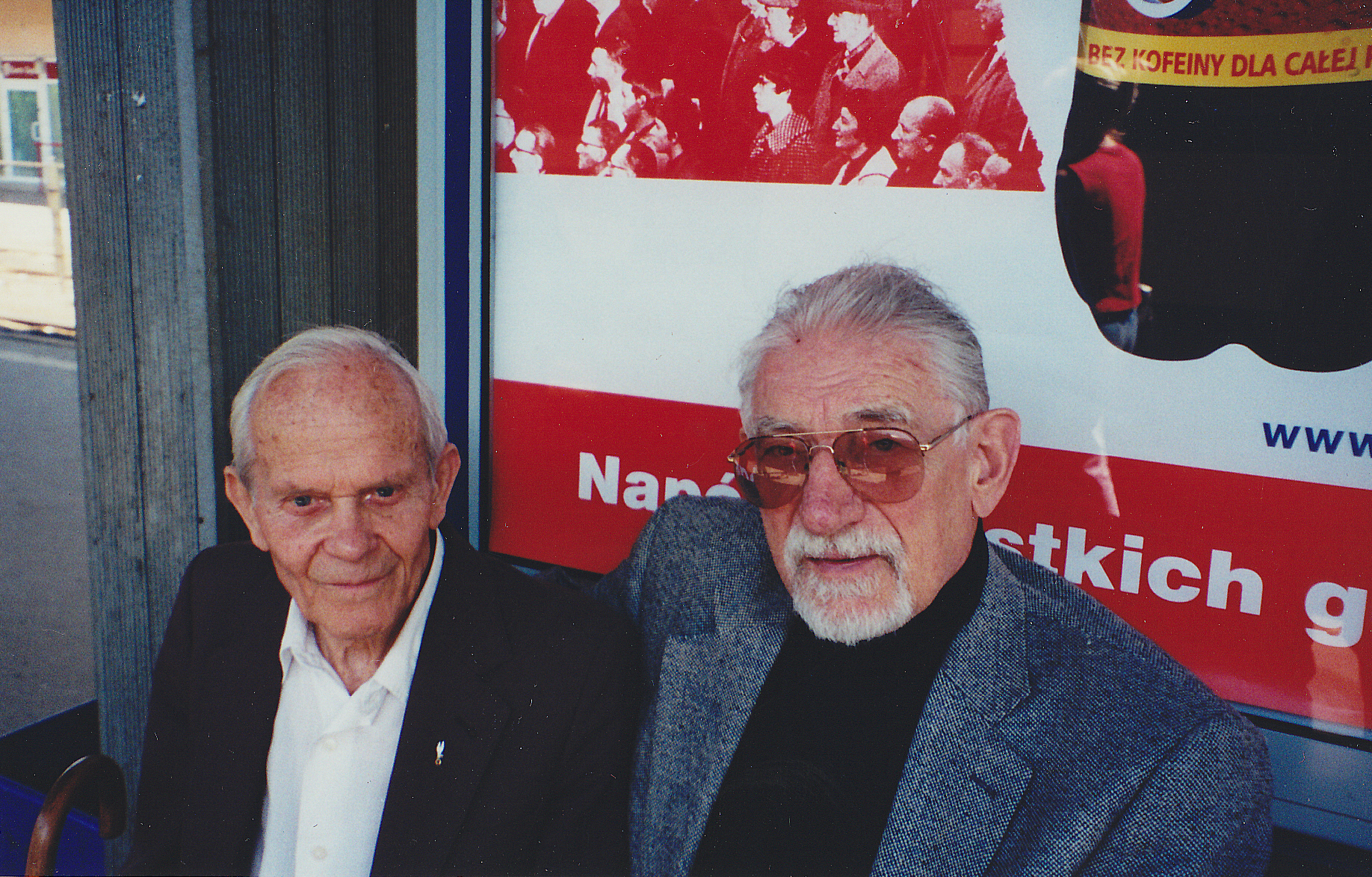

Bartek wrote his last words after the 50th commemin 1994, where he saw his best friend Sławek from the war in Driel, whom he had lost sight of after 1953.

Want to read this story yourself?

Would you like to read Bartek Mazur’s experiences yourself? The English-language book is in the US available via Ebay (but comes with almost double the amount of shippingcosts.

In the Netherlands it is available for €25 at lectures that we give together with the Driel Polen Foundation. Can’t wait for that? Send an email via our contactform.

Please include your name and address in the Netherlands. For sending by post, we do charge an additional €5 to cover shipping costs. We will of course first send you an email explaining how you can pay for the book.

Photos courtesy of Edina Mazur

This article was first published in Dutch on Polen in Beeld.